The picture is ubiquitous in American culture: a gigantic, cardboard check, inscribed with an exorbitant sum of money, and a seemingly miniscule face emerging from the top. The face’s sheepish grin is somehow half-elation and half-confusion as it processes the life-changing money it just unexpectedly received.

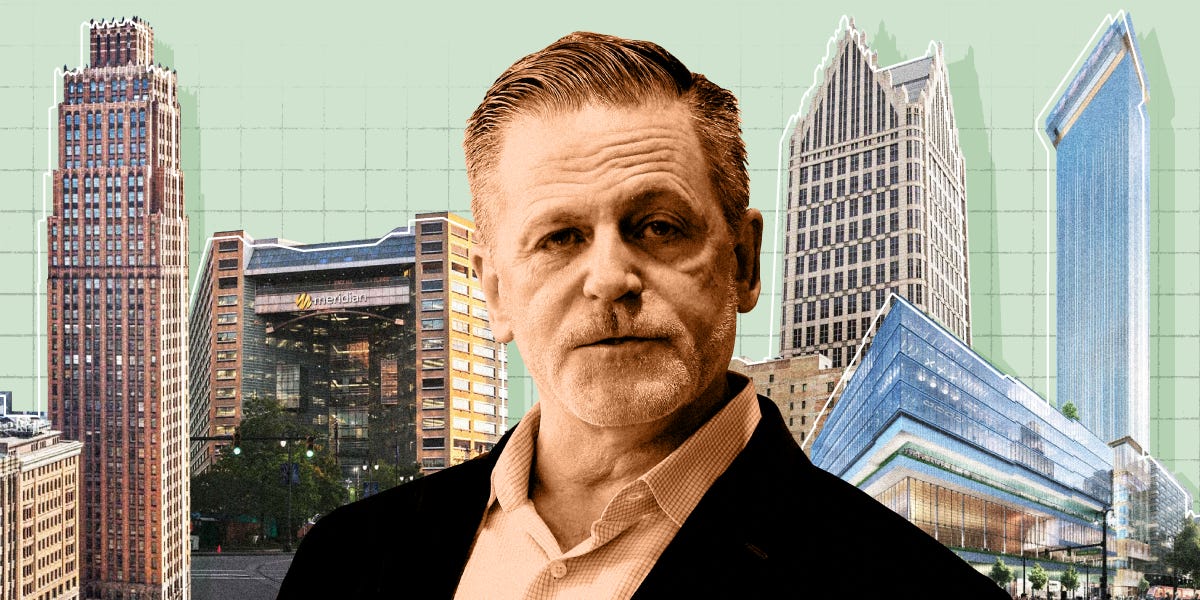

Detroit, Michigan found itself in this exact position on March 25, 2021. Dan Gilbert, the chairman of Quicken Loans, donated $500 million to revitalize the Detroit metropolitan area. The grant includes immediate tax relief for about 20,000 at-risk families, home repairs for low income citizens, and digital infrastructure for an increasingly modern world.

Detroit, once the pinnacle of American manufacturing, has been trapped in a half-century-long tumble from the peak of prosperity. And it has been a bumpy ride down. As foreign cars gained an increasing market share, Detroit’s automotive industry hemorrhaged jobs. This effect was exacerbated by American car manufacturers exporting much of their labor in a frantic chase towards cheaper prices and larger profit margins. As Fords and GMCs were replaced with Mazdas and Porsches on American roads, Detroit rusted from a gleaming metropolis into an aging, steel pimple on American maps. And its citizens, once locked into steady, high-paying jobs, bore the brunt of Detroit’s sharp decline.

Although the auto industry is gradually recovering, Detroit is still reeling from the 2008 financial crisis when a number of its car manufacturers went bankrupt. After this journey into oblivion, Detroit desperately needs Dan Gilbert’s millions. That is the wholesome version of this story that will undoubtedly implore many to comment that it ‘restores their faith in humanity,’ or something like that. On the other hand, Dan Gilbert might have just opened a porthole into a grim, not-so-distant future as we sail towards a capital-feudalist world.

If you got into one of those Detroit-manufactured cars and drove on Interstate 44, about 13 hours later you would arrive in Bentonville, Arkansas. With about $100 dollars in gas released into the atmosphere, you would step into a city (a town, really) with less than 10% population of the population of Detroit. You might explore the cozy but growing downtown. You might relax in a perfectly manicured park. You might learn about Native American culture at the Museum of Native American History.

However, maybe, you would feel like something is a bit off. That feeling would be the comforting uneasiness that comes from standing in an outdoor Walmart. The downtown, the grass — it is all paid for by Walmart. 15 years ago, Walmart started funding local projects through its philanthropic wing, simultaneously enjoying the tax breaks resulting from their generosity and accumulating control over a city that was willing to forfeit its democratic independence. In the last decade and a half, Walmart cash transformed Bentonville in a really great place to live. That impressive downtown, new-urbanist city planning, and an elite private school — all specifically bankrolled by Walmart — helped the corporation recruit the best employees and executives. Therefore, as Bentonville economically develops, Walmart increases their return on investment. Every dollar you might spend during your excursion actually sustains Walmart’s bourgeois utopia in the Northwest corner of the union’s 3rd poorest state.

As corporations evolved into monopolies during the 19th century, many employed vertical integration as the means to that end. Corporatist cities — in which we are housed, fed, and entertained according to our rank within a company — seem like a natural extension of this tried and true method. And Walmart’s Bentonville experiment seems like a step in that direction.

Gilbert’s project, if it follows in these footsteps, would be a much larger and grotesque trial. Fortunately, there is ample evidence that a corporate city is not Gilbert’s intention. This particular $500 million is the latest in the string of Gilbert’s donations for Detroit (although previous donations financed the downtown, not the entire metro area). Gilbert even served on an Obama commission tasked with revitalizing Detroit in the wake of the Great Recession. Most comforting perhaps, is that Gilbert’s donation is personal, and not directly tied to Quicken Loans. In this case, it seems like the heartwarming version is truly reality. It is however, dangerously close to Walmart’s dystopian example.